|

||||||

|

GAY

FILM REVIEWS BY MICHAEL D. KLEMM

|

||||||

|

Johan: Waterbearer Films,

Director: Screenplay: Staring: Unrated, 85 minutes |

Another

From

Johan: Mon ete 75, which is billed as "a French classic, complete and unseen since 1976," is one of the most sexually explicit art films I have ever seen. The day after seeing it, I watched Wrangler: Anatomy of an Icon, a new documentary about 70s adult film star, Jack Wrangler. The timing couldn't have been better because one of the talking heads commented how the early gay porn directors had more artistic aspirations than those today. He cited the lyrical photography of model Casey Donovan in the soft core 1971 Wakefield Poole film, Boys in the Sand, to make his point. |

The

reason that I mention this is because the same style of sensual imagery

permeates director Philippe Vallois'

Johan: Mon ete 75, and the film

resembles a strange hybrid of Poole and Jean Luc Godard. Johan

was made during a time when Europe was pioneering films that explored frank,

and often explicit, sexuality. Blow Up, I Am Curious (Yellow), Last Tango

In Paris and others were landmarks that pushed the envelope. It was

time for a gay filmmaker to do the same. The

reason that I mention this is because the same style of sensual imagery

permeates director Philippe Vallois'

Johan: Mon ete 75, and the film

resembles a strange hybrid of Poole and Jean Luc Godard. Johan

was made during a time when Europe was pioneering films that explored frank,

and often explicit, sexuality. Blow Up, I Am Curious (Yellow), Last Tango

In Paris and others were landmarks that pushed the envelope. It was

time for a gay filmmaker to do the same. |

|

|

|

|

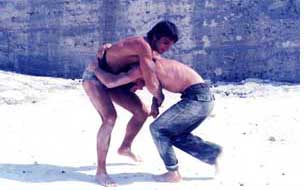

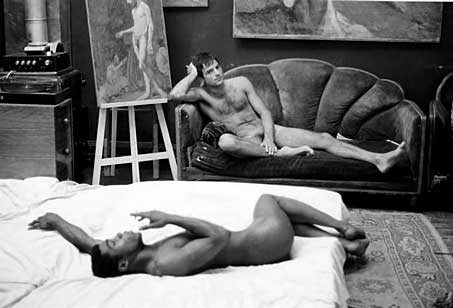

Frequenting

the cruising grounds in the Tuileries Gardens, Phillipe attempts to recreate

his idyll with a string of attractive Parisian men. At the same time, his

journey intersects with a variety of worlds that expand his horizons. One

of his young actors describes his role as a "sadist" in S&M clubs, another

explains the functions of his sex toys and gives a demonstration of fisting.

Phillipe enjoys an interracial romance and their love scenes are the sexiest

in the film. Interspersed throughout are lovingly lit exterior shots that

celebrate the beauty of the male physique. A man dances nude in front of

a wall of paintings; two shirtless legionnaires wrestle and then fuck in

the desert; two men dressed as Arabian princes sit on horseback in a campy

tableaux ala Pink Narcissus or Kenneth

Anger. Frequenting

the cruising grounds in the Tuileries Gardens, Phillipe attempts to recreate

his idyll with a string of attractive Parisian men. At the same time, his

journey intersects with a variety of worlds that expand his horizons. One

of his young actors describes his role as a "sadist" in S&M clubs, another

explains the functions of his sex toys and gives a demonstration of fisting.

Phillipe enjoys an interracial romance and their love scenes are the sexiest

in the film. Interspersed throughout are lovingly lit exterior shots that

celebrate the beauty of the male physique. A man dances nude in front of

a wall of paintings; two shirtless legionnaires wrestle and then fuck in

the desert; two men dressed as Arabian princes sit on horseback in a campy

tableaux ala Pink Narcissus or Kenneth

Anger. |

|

|

But when the mike boom invades a monochromatic scene as well, you begin to question the film's reality. There are at least two erotic interludes in which Phillipe tricks with another man but he is played by a different actor. Are these also scenes from the movie he is making? Or are we in the director's mind as he visualizes his script? The filmmaker is being deliberately vague. Johan, who is never seen by the way, has a round tattoo on his forehead. Each actor who plays him will sport the same tattoo, as will his lady friend Christine and finally Phillipe, himself, when he decides that only he knows Johan well enough to be able to play him onscreen. |

|

|

|

| The film covers a lot of ground, perhaps too much and the action is often meandering as it drifts from one scene to the next. A lengthy flashback set in New York City, involving a brief romance with an expatriate Cuban poet, provides a nice diversion but one that could have almost have been a seperate movie by itself. | |

Johan

was actually screened uncut at the 1976 Cannes Film Festival. The French

censors, however, slapped an X rating on the film and the naughtier bits

(like the fisting scene) were edited for general release. The negative was

destroyed and the film itself vanished from view for years. It was rarely

screened, and was eventually forgotten; there is no mention of Johan

in any of my queer film texts. On the documentary that comes with the disc,

director Vallois tells how a French film archive discovered a small reel

labeled "Johan" that was forgotten in a projection booth 30 years before.

It contained all the footage, long thought to be lost, that was cut to avoid

the X rating. All the explicit imagery that the audience saw at Cannes has

been lovingly restored and a new generation can see the film as it was originally

screened. Johan

was actually screened uncut at the 1976 Cannes Film Festival. The French

censors, however, slapped an X rating on the film and the naughtier bits

(like the fisting scene) were edited for general release. The negative was

destroyed and the film itself vanished from view for years. It was rarely

screened, and was eventually forgotten; there is no mention of Johan

in any of my queer film texts. On the documentary that comes with the disc,

director Vallois tells how a French film archive discovered a small reel

labeled "Johan" that was forgotten in a projection booth 30 years before.

It contained all the footage, long thought to be lost, that was cut to avoid

the X rating. All the explicit imagery that the audience saw at Cannes has

been lovingly restored and a new generation can see the film as it was originally

screened. |

|

| This is not my first encounter with the filmmaker. 10 years ago, one of the first films that I reviewed for Outcome was a later title from the same director. It was an off-beat World War II drama, entitled We Were One Man, in which a village half-wit finds a wounded Nazi soldier and takes him back to his cottage. While not quite as convoluted as his first feature film, this one also threw conventional narrative out the window. | |

Vallois

wanted cinema to celebrate male sensuality and Johan

erupts with passion. While explicit, its honesty and gritty realism transcends

the pornographic. Johan was lightyears

ahead of its time - consider, for example, how gay men were being routinely

portrayed in Hollywood films. For those who would dismiss the film as being

just "artsy porn," the director has captured a long gone era of pre-AIDS

gay liberation and the queer milieu of 1970s Paris is carved into celluloid

forever just as the British film Nighthawks

(1978) would preserve the London nightlife and even

Cruising (1980), in its own way, left us with a document of the

New York meat packing district leather scene. Vallois

wanted cinema to celebrate male sensuality and Johan

erupts with passion. While explicit, its honesty and gritty realism transcends

the pornographic. Johan was lightyears

ahead of its time - consider, for example, how gay men were being routinely

portrayed in Hollywood films. For those who would dismiss the film as being

just "artsy porn," the director has captured a long gone era of pre-AIDS

gay liberation and the queer milieu of 1970s Paris is carved into celluloid

forever just as the British film Nighthawks

(1978) would preserve the London nightlife and even

Cruising (1980), in its own way, left us with a document of the

New York meat packing district leather scene. |

|

|

More

on Philippe Vallois: See also: See also:

Similar

films:

|