|

||||||

|

GAY

FILM REVIEWS BY MICHAEL D. KLEMM

|

||||||

|

The

Witnesses Strand

Releasing, Director: Screenplay: Starring: Unrated, 112 minutes

A

Year Without Love Director: Screenplay: Starring Unrated, 95 minutes |

Journal

Of the

In 1994, French director Andre Techine fathered a delightful film entitled Wild Reeds; a microcosm of the French-Algerian conflict told through the sexual awakenings (both gay and straight) of a small circle of students. Wild Reeds was a film of great lyrical beauty on par with the best of Truffaut. Techine's newest film, The Witnesses, is set during another period of great upheaval. The year is 1984 and the setting is Paris. It is a carefree time; a sexual revolution is in full bloom. The Witnesses chronicles the connections between a group of friends whose lives are thrown into a tailspin when a "mysterious disease from the West" rears its ugly head. |

Manu

(Johan Libereau) is a cute young boytoy who has just come to Paris to live

with his sister, Julie (Julie Depardieu). She is an aspiring opera singer

who resides in a seedy hotel. Greeting her brother, she remarks that he

is "as narcissistic as ever." Later, strolling through a gay cruising park,

Manu meets Adrien, (Michel Blanc), a 50-ish doctor. Manu thinks Adrien is

too old and seeks out fresher meat, but then imposes on the doctor to guard

his coat while he goes trysting in the trees. Adrien is smitten by the impulsive

young lad and his willingness to trust him. He takes Manu under his wing,

wining and dining him and showing him the sights of Paris. Manu

(Johan Libereau) is a cute young boytoy who has just come to Paris to live

with his sister, Julie (Julie Depardieu). She is an aspiring opera singer

who resides in a seedy hotel. Greeting her brother, she remarks that he

is "as narcissistic as ever." Later, strolling through a gay cruising park,

Manu meets Adrien, (Michel Blanc), a 50-ish doctor. Manu thinks Adrien is

too old and seeks out fresher meat, but then imposes on the doctor to guard

his coat while he goes trysting in the trees. Adrien is smitten by the impulsive

young lad and his willingness to trust him. He takes Manu under his wing,

wining and dining him and showing him the sights of Paris. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This

is an amazing ensemble film, juggling multiple characters and storylines

while dramatizing the confusion and terror manifest during the early days

of the AIDS pandemic. This was a time that young audiences, half my age,

didn't live through... when almost nothing was known about the disease and

those who developed full-blown AIDS often died within months of their diagnosis.

Manu's illness will have far-reaching repercussions for each of the principals.

Adrien, who has already been studying this new disease with a coalition

of other doctors, becomes Manu's physician and caregiver, while Mehdi fears

that he is also infected and may have also given the virus to his wife. This

is an amazing ensemble film, juggling multiple characters and storylines

while dramatizing the confusion and terror manifest during the early days

of the AIDS pandemic. This was a time that young audiences, half my age,

didn't live through... when almost nothing was known about the disease and

those who developed full-blown AIDS often died within months of their diagnosis.

Manu's illness will have far-reaching repercussions for each of the principals.

Adrien, who has already been studying this new disease with a coalition

of other doctors, becomes Manu's physician and caregiver, while Mehdi fears

that he is also infected and may have also given the virus to his wife.

|

|

|

Before you say that this sounds depressingly familiar, The Witnesses doesn't follow the standard formula of most past AIDS films. The emphasis here is not on the suffering and eventual death of one protagonist, nor is it about a collection of identifiable types (the slut, the cuckolded lover, the gym rat, the showtune queen) who all succumb, one by one, to the virus. Techine eschews operatic excess in favor of quiet character-driven drama and The Witnesses has great characters in abundance. |

|

Life

is never black and white; humans are a mass of contradictions and it is

a joy to sometimes actually see this depicted believably in the movies.

Take, for example, Sarah who writes children's books but wishes she never

had a child. Obsessed with finishing her new novel, she wears earplugs as

she types so that she doesn't hear the baby crying. Her husband, Mehdi,

is a star player with the vice squad. Primarily targeting prostitution,

he is not above raiding the gay bars and cruising parks. A punkish hooker,

who lives in the same flophouse as Manu and his sister, calls Mehdi " a

man on a mission." Even so, he falls under Manu's spell, enjoying daily

trysts and sometimes even bottoming for the young Casanova. Mehdi

enjoys an open relationship with Sarah, who doesn't care who he sleeps

with, as long as she can work on her book. But, if he has been infected

by his assignations with Manu, how is he going to explain this, not just

to his wife, but also to his fellow vice cops? Life

is never black and white; humans are a mass of contradictions and it is

a joy to sometimes actually see this depicted believably in the movies.

Take, for example, Sarah who writes children's books but wishes she never

had a child. Obsessed with finishing her new novel, she wears earplugs as

she types so that she doesn't hear the baby crying. Her husband, Mehdi,

is a star player with the vice squad. Primarily targeting prostitution,

he is not above raiding the gay bars and cruising parks. A punkish hooker,

who lives in the same flophouse as Manu and his sister, calls Mehdi " a

man on a mission." Even so, he falls under Manu's spell, enjoying daily

trysts and sometimes even bottoming for the young Casanova. Mehdi

enjoys an open relationship with Sarah, who doesn't care who he sleeps

with, as long as she can work on her book. But, if he has been infected

by his assignations with Manu, how is he going to explain this, not just

to his wife, but also to his fellow vice cops? |

|

The

first act, subtitled: Happy Days, Summer 1984, ebbs into act two:

War, Winter 1984-5 and the sunny opening hour contrasts with the

tragic second half. Dark comedy co-exists with the drama and no story arc,

not even Manu's illness, is milked for pathos. In fact, many of the big

moments, as when Manu learns of his condition, are often dispensed with

by a few lines of Sarah's ironic narration (which may or may not be from

the book she is writing.). The script is a marvel. My only criticism might

be that it goes on for a bit too long at the end without a good bang, as

Salieri would describe to Mozart in Amadeus, to let the audience

know when to clap. But a true artist like Mozart trusts his audience. I

think that was the filmmakers' intention; to show how life goes on and that

the loose strands are never tied up with a big red bow. The

first act, subtitled: Happy Days, Summer 1984, ebbs into act two:

War, Winter 1984-5 and the sunny opening hour contrasts with the

tragic second half. Dark comedy co-exists with the drama and no story arc,

not even Manu's illness, is milked for pathos. In fact, many of the big

moments, as when Manu learns of his condition, are often dispensed with

by a few lines of Sarah's ironic narration (which may or may not be from

the book she is writing.). The script is a marvel. My only criticism might

be that it goes on for a bit too long at the end without a good bang, as

Salieri would describe to Mozart in Amadeus, to let the audience

know when to clap. But a true artist like Mozart trusts his audience. I

think that was the filmmakers' intention; to show how life goes on and that

the loose strands are never tied up with a big red bow. |

|

The

acting by all is superb. Special praise to Michel Blanc, who beautifully

embodies Adrien's tragedy without becoming pathetic or maudlin. Played as

a cross between Felix Unger and Donald Pleasance, he is noble and flawed,

wise and deluded, and an utterly compelling character. Johan Libereau, as

Manu, is adorable without being boy-band-cute. His wide-eyed innocence is

infectious. He is a young man who, in many ways, is still a boy and this

makes his fate all the more tragic. He recalls how he never bruised when

he got beat up in school, and now he is helpless and dying of a disease

that he has never even heard of before now. Emmanuelle Beart is both

icy and manic as Sarah. Sami Bouajila's Mehdi is testosterone incarnate

and made of stone, but vulnerable beneath in a way not unlike Brando in

A Streetcar Named Desire. One of the film's best moments is reserved

for him when he learns of Manu's illness, breaks down the moment he is alone,

and then sits in a laundromat and stares, in a Zen-like trance, at the tumbling

clothes in a washing machine's window. The

acting by all is superb. Special praise to Michel Blanc, who beautifully

embodies Adrien's tragedy without becoming pathetic or maudlin. Played as

a cross between Felix Unger and Donald Pleasance, he is noble and flawed,

wise and deluded, and an utterly compelling character. Johan Libereau, as

Manu, is adorable without being boy-band-cute. His wide-eyed innocence is

infectious. He is a young man who, in many ways, is still a boy and this

makes his fate all the more tragic. He recalls how he never bruised when

he got beat up in school, and now he is helpless and dying of a disease

that he has never even heard of before now. Emmanuelle Beart is both

icy and manic as Sarah. Sami Bouajila's Mehdi is testosterone incarnate

and made of stone, but vulnerable beneath in a way not unlike Brando in

A Streetcar Named Desire. One of the film's best moments is reserved

for him when he learns of Manu's illness, breaks down the moment he is alone,

and then sits in a laundromat and stares, in a Zen-like trance, at the tumbling

clothes in a washing machine's window. |

|

|

After spending the

last year mired in mediocre movies, The Witnesses

(and a few others like The Bubble and

Go West) has restored my faith in queer

cinema. This one would have been at home in one my college film classes.

This is one of the finest films, gay or straight, that I have seen in

a long time.

|

|

|

|

| A recent Spanish import, entitled A Year Without Love, is another film of considerable merit. Based on a memoir published by poet Pablo Perez, first-time director Anahi Berneri's edgy film adaptation, set in 1996 Buenos Aires, adds an unusual spin to what could have been just another tug-at-the-heartstrings AIDS drama. Juan Minujin plays Pablo, a young poet who has tested positive and is starting to get sick. He refuses his AZT medication, telling his doctor that "I won't play guinea pig for you while you try to get the right dose." Believing that his days are few, he begins keeping a journal. He also continues to live his life, placing personal ads in magazines and cruising the early internet. Thumbing his nose at his illness, he throws on a leather jacket one night and goes out to the bars even though, moments before, he lay coughing in his bed. | |

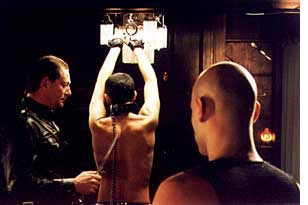

Online

assignations lead to a meeting with "Leather couple seeks threesome." Pablo

becomes the guest of the Sheriff, a major player in the local S&M scene.

Our young poet explains that he has had some experience in the leather bars

of Paris when he lived abroad. Family matters forced his return to Buenos

Aires; he left a lover behind and wasn't in Paris when he died. Guilt-ridden,

aching for love and scared of dying, he submits to the Sheriff; accepting

the lash across his back as he learns to eroticize his pain. Online

assignations lead to a meeting with "Leather couple seeks threesome." Pablo

becomes the guest of the Sheriff, a major player in the local S&M scene.

Our young poet explains that he has had some experience in the leather bars

of Paris when he lived abroad. Family matters forced his return to Buenos

Aires; he left a lover behind and wasn't in Paris when he died. Guilt-ridden,

aching for love and scared of dying, he submits to the Sheriff; accepting

the lash across his back as he learns to eroticize his pain. |

|

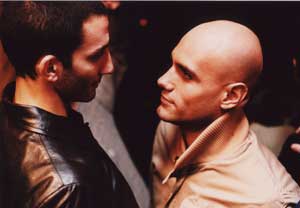

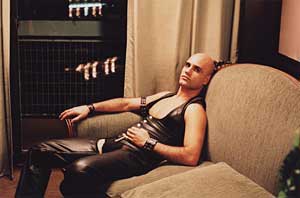

Pablo's

odyssey is a dark story, leavened here and there with bits of humor. There

are hints at a possible love story; Pablo falls for a hot young leather

master, with a shaved head, named Martin (Javier van de Couter). It's hard

to tell if the feeling is mutual beyond the intense sexual attraction, established

in two early scenes, when the men made eye contact as they pass in the entrance

to a gay bar and later on the street outside the Sheriff's apartment building.

Their first tryst is rather romantic, their second involves flogging. Pablo's

odyssey is a dark story, leavened here and there with bits of humor. There

are hints at a possible love story; Pablo falls for a hot young leather

master, with a shaved head, named Martin (Javier van de Couter). It's hard

to tell if the feeling is mutual beyond the intense sexual attraction, established

in two early scenes, when the men made eye contact as they pass in the entrance

to a gay bar and later on the street outside the Sheriff's apartment building.

Their first tryst is rather romantic, their second involves flogging. |

|

This

concept will be alien to many viewers. An open mind is essential because

the leather and bondage scenes, as depicted here, are quite explicit. They

aren't, however, exploitative. This isn't porn but it's also definitely

not for the prudish or squeamish. One scene, in particular, is both erotic

and terrifying at once. Designed for mature audiences, this is not a television

"disease of the week" flick. This is also a film that would never get green-lighted

in Hollywood - where it is acceptable to have carnal relations with an apple

pie but a male love story is still considered box office poison (despite

the success of Brokeback

Mountain). What I found the most interesting about A

Year Without Love was the way that the S&M world was not,

for a change, depicted as a criminal underworld (8MM) menacing (Cruising),

or played for laughs (Exit to Eden) as it usually is in most films,

straight and gay. This

concept will be alien to many viewers. An open mind is essential because

the leather and bondage scenes, as depicted here, are quite explicit. They

aren't, however, exploitative. This isn't porn but it's also definitely

not for the prudish or squeamish. One scene, in particular, is both erotic

and terrifying at once. Designed for mature audiences, this is not a television

"disease of the week" flick. This is also a film that would never get green-lighted

in Hollywood - where it is acceptable to have carnal relations with an apple

pie but a male love story is still considered box office poison (despite

the success of Brokeback

Mountain). What I found the most interesting about A

Year Without Love was the way that the S&M world was not,

for a change, depicted as a criminal underworld (8MM) menacing (Cruising),

or played for laughs (Exit to Eden) as it usually is in most films,

straight and gay. |

|

A

full portrait of the artist greets the audience. We learn that, as a boy,

he began to write by pretending that he was the ghost of famed Chilean poet,

Pablo Nerudo, when he and his aunt played with a Ouija board. He shares

a flat with the same aunt, now senile, the rent is paid by his indifferent

father and, to make ends meet, Pablo tutors students in French. We meet

Pablo's best friend, we meet his doctors, several very friendly leather

men, an amorous female pupil, and his publisher - who sees more commercial

potential in a diary of Pablo's illness than a volume of his poetry. Small

character touches abound, like his aunt amusedly flipping through one of

his porn magazines when he's not looking, or super leather stud Martin still

living at home with his parents. A

full portrait of the artist greets the audience. We learn that, as a boy,

he began to write by pretending that he was the ghost of famed Chilean poet,

Pablo Nerudo, when he and his aunt played with a Ouija board. He shares

a flat with the same aunt, now senile, the rent is paid by his indifferent

father and, to make ends meet, Pablo tutors students in French. We meet

Pablo's best friend, we meet his doctors, several very friendly leather

men, an amorous female pupil, and his publisher - who sees more commercial

potential in a diary of Pablo's illness than a volume of his poetry. Small

character touches abound, like his aunt amusedly flipping through one of

his porn magazines when he's not looking, or super leather stud Martin still

living at home with his parents. |

|

A

keen eye for the image is at work here. Many visual parallels are drawn,

contrasting the bondage settings with hospital examinations. A close-up

of an arm penetrated by a needle, and an X-ray grid projected onto Pablo's

bare back, will look just as creepy to some as the poster art's dagger caressing

that same flesh. The hospital scenes are sterile, drained of all color while

a dark S&M orgy, glimpsed in brief flashes, is warm, womblike and mysterious. A

keen eye for the image is at work here. Many visual parallels are drawn,

contrasting the bondage settings with hospital examinations. A close-up

of an arm penetrated by a needle, and an X-ray grid projected onto Pablo's

bare back, will look just as creepy to some as the poster art's dagger caressing

that same flesh. The hospital scenes are sterile, drained of all color while

a dark S&M orgy, glimpsed in brief flashes, is warm, womblike and mysterious. |

|

| Though A Year Without Love is not without its flaws, it remains compelling cinema. Pablo eventually submits to the new AIDS cocktails and responds to the treatment but family strife provides a bit of third act drama before the film comes to a very abrupt conclusion. Reportedly, the ending (or lack thereof) mirrors author Perez's diary, that ended as the year did, but a bit of a cinematic coda - even a freeze frame of Pablo's face or perhaps a title card to announce that this was based on a true story - would have provided dessert to a heavy meal. | |

|

More

on Andre Techine: Carlos Echevarria also appears in: |