|

Keep The Lights On

Music Box Films,

2012

Director:

Ira Sachs

Screenplay:

Ira Sachs,

Mauricio Zacharias

Starring;

Thure Lindhardt,

Zachary Booth,

Julianne Nicholson, Souleymane

Sy Savane,

Paprika Steen,

Maria Dizzia, Sebastian La Cause

Unrated,

101 minutes |

Good Times,

Bad Times

by

Michael D. Klemm

Posted online June, 2013

Even the worst marriages usually begin with throes of passion. And then paradise by the dashboard light turns into praying for the end of time. Gone is the spark. The good times and the bad are remembered; the mundane moments in-between forgotten. These vivid flashes are what we call memory. Ira Sachs has mined these memories and turned them into art in his autobiographical film, Keep The Lights On (2012). Hemingway once famously said that one should only write about what one knows, and this film is a small revelation. |

Longtime relationships have their ups and downs but this one is an old and shaky, wooden rollercoaster and its riders feel every rattle and bump. No one should have to endure emotional overload on this scale. Erik and Paul both have issues. Throw drug addiction into the mix and the drama goes into warp drive. Longtime relationships have their ups and downs but this one is an old and shaky, wooden rollercoaster and its riders feel every rattle and bump. No one should have to endure emotional overload on this scale. Erik and Paul both have issues. Throw drug addiction into the mix and the drama goes into warp drive.

|

|

The audience is invited to eavesdrop on these two men over the course of ten years and experience both their joy and their pain. Erik (Thure Lindhardt) and Paul (Zachary Booth) hook up on a phone sex line late one night. Erik goes to Paul’s apartment in Chelsea. The sexual attraction is immediate; they kiss without even first saying hello. The camera lingers for a moment on the initial passion and then abruptly cuts to the bedroom for a fairly explicit sexual frolic. Erik leaves his phone number. “I have a girl friend,” Paul confesses, “So don’t get your hopes up.” Erik says, “That’s too bad” and they keep looking at each other. The audience is invited to eavesdrop on these two men over the course of ten years and experience both their joy and their pain. Erik (Thure Lindhardt) and Paul (Zachary Booth) hook up on a phone sex line late one night. Erik goes to Paul’s apartment in Chelsea. The sexual attraction is immediate; they kiss without even first saying hello. The camera lingers for a moment on the initial passion and then abruptly cuts to the bedroom for a fairly explicit sexual frolic. Erik leaves his phone number. “I have a girl friend,” Paul confesses, “So don’t get your hopes up.” Erik says, “That’s too bad” and they keep looking at each other.

|

|

Paul may have a girl friend but he obviously prefers the company of men. He and Erik see more of each other and eventually move in together. Aside from a nicely comic scene where the guys run into her in an art gallery, Paul’s girl friend is never heard from again. Now we can just concentrate on the guys. Erik and Paul are hot for each other, as the numerous sex scenes make clear. Even when things get bad, the sex is usually still great. For now, their relationship is idyllic without being nauseating. But Paul is soon revealed to be a crackhead and his escalading drug use will test the bonds of their marriage. |

Erik is a documentary filmmaker of some acclaim. He has been working for years on his latest subject – a forgotten, underground director, named Avery Willard, who began making short queer films in the 40s and 50s. (I never heard of him before either.) Sometimes the work consumes him at the expense of his relationships. His sister berates him for turning down a job at PBS and asks if their father is paying for this film too. “In your 20s, it’s charming to be up and coming,” she sneers, “In your 30s, it’s pathetic.” Paul is a lawyer at Random House. He has a job and he reminds Erik of this almost every time that they have a fight. Erik is a documentary filmmaker of some acclaim. He has been working for years on his latest subject – a forgotten, underground director, named Avery Willard, who began making short queer films in the 40s and 50s. (I never heard of him before either.) Sometimes the work consumes him at the expense of his relationships. His sister berates him for turning down a job at PBS and asks if their father is paying for this film too. “In your 20s, it’s charming to be up and coming,” she sneers, “In your 30s, it’s pathetic.” Paul is a lawyer at Random House. He has a job and he reminds Erik of this almost every time that they have a fight.

|

|

Paul’s drug use spirals out of control and sometimes he disappears for days. Erik isn’t handling it well. “You’re killing me!” he screams into his phone when he gets his absent partner’s voice mail again. Finally, an intervention is staged. A stint in rehab, Paul is home for Christmas, and everything’s coming up roses again. The film allows them this one happy scene together before things take a nosedive again. |

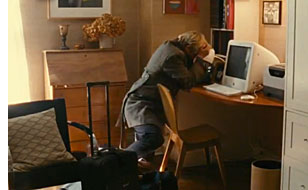

Some of this is pretty harrowing, and hard to watch. The film achieves almost unbearable intensity when Paul vanishes on a three week drug binge. Erik is basking in the glory of winning the Teddy award for best documentary at the Berlin Film Festival. Elated, he calls Paul and leaves a message that is never returned. Erik returns home, frantic, to an empty apartment. In the most powerful use of an answering machine as a dramatic device that I have ever seen, Erik hits “play” and collapses while listening to his unheard message from Berlin, followed by dozens of others. It’s hard to face the fact that your man loves crack cocaine more than he loves you. Some of this is pretty harrowing, and hard to watch. The film achieves almost unbearable intensity when Paul vanishes on a three week drug binge. Erik is basking in the glory of winning the Teddy award for best documentary at the Berlin Film Festival. Elated, he calls Paul and leaves a message that is never returned. Erik returns home, frantic, to an empty apartment. In the most powerful use of an answering machine as a dramatic device that I have ever seen, Erik hits “play” and collapses while listening to his unheard message from Berlin, followed by dozens of others. It’s hard to face the fact that your man loves crack cocaine more than he loves you.

|

Rough stuff. But even a tragedy needs to lighten up now and then. My favorite comic moment: Erik has gone away to a week-long artist’s retreat to edit his film. Taking a much needed break, he calls a phone sex line – and winds up talking to Paul. (Their subsequent fight is laugh out loud funny.) There are two scenes where Erik hooks up with a bodybuilder who is more interested in posing than fucking. When Paul is in rehab, a drunken Erik makes out with a man named Igor in a gay bar men’s room – and then vomits on the floor. (Clearly, Erik also isn’t behaving himself. Ignoring Paul when he works on his film probably hasn’t helped their marriage either.) Rough stuff. But even a tragedy needs to lighten up now and then. My favorite comic moment: Erik has gone away to a week-long artist’s retreat to edit his film. Taking a much needed break, he calls a phone sex line – and winds up talking to Paul. (Their subsequent fight is laugh out loud funny.) There are two scenes where Erik hooks up with a bodybuilder who is more interested in posing than fucking. When Paul is in rehab, a drunken Erik makes out with a man named Igor in a gay bar men’s room – and then vomits on the floor. (Clearly, Erik also isn’t behaving himself. Ignoring Paul when he works on his film probably hasn’t helped their marriage either.)

|

|

Keep The Lights On rings with truths that can only come from personal experience. Writer/director Ira Sachs wisely worked with a second writer, Mauricio Zacharias, who helped to edit and shape his life into a dramatic and cohesive story. They are adept at capturing all the nuances of a relationship; especially the small annoyances that escalate into knockout fights and long held grudges. Never self indulgent or melodramatic, Keep The Lights On hits all the right notes. Sachs’ directorial hand is firm, the cinematography is beautiful, and the acting is superb. Oh, and lest one think Sachs is airing dirty laundry, his ex, Bill Clegg, wrote about his addiction in his own confessional memoir, Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man. Making this film must have been catharsis for the director. |

Lindhardt convincingly conveys Erik’s pain and helplessness. He could be Liv Ullmann in one of Ingmar Bergman’s angst-fests. As a stand-in for the director, Erik might be the main character but his co-star is also a dominant force. As Paul, Booth ably projects all the conflicting traits of a user from boyish charm to selfish tantrums to silent cries for help. They are well served by a perfect supporting cast. I didn’t write about a few small subplots. My review’s focus, like the film’s, is on Erik and Paul… but the script’s little touches add spice and flavor to the main course. Lindhardt convincingly conveys Erik’s pain and helplessness. He could be Liv Ullmann in one of Ingmar Bergman’s angst-fests. As a stand-in for the director, Erik might be the main character but his co-star is also a dominant force. As Paul, Booth ably projects all the conflicting traits of a user from boyish charm to selfish tantrums to silent cries for help. They are well served by a perfect supporting cast. I didn’t write about a few small subplots. My review’s focus, like the film’s, is on Erik and Paul… but the script’s little touches add spice and flavor to the main course.

|

Keep The Lights On has garnished much crossover acclaim. It is a good thing to see such visibility in the mainstream; more and more reviewers and audiences are recognizing the universal themes and not pigeon-holing these movies as just “gay films.” Keep The Lights On, and also Andrew Haigh’s Weekend, were given rave reviews by the late Roger Ebert last year. Ira Sachs won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in 2005 for his Forty Shades of Blue and Keep The Lights On can only strengthen his reputation further. I cannot recommend this remarkable movie enough. Keep The Lights On has garnished much crossover acclaim. It is a good thing to see such visibility in the mainstream; more and more reviewers and audiences are recognizing the universal themes and not pigeon-holing these movies as just “gay films.” Keep The Lights On, and also Andrew Haigh’s Weekend, were given rave reviews by the late Roger Ebert last year. Ira Sachs won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in 2005 for his Forty Shades of Blue and Keep The Lights On can only strengthen his reputation further. I cannot recommend this remarkable movie enough.

|

Life got in the way last year and I wasn’t able to review many films. While I was neglecting my website, queer cinema seems to have entered a new Renaissance. Along with August and especially Weekend, (my next review), Keep The Lights On is one of the best new queer narrative films I’ve seen in years. When my Dad died, my writing began to get more sporadic. I also started getting disillusioned by most of the new queer films that I did see. It’s not that they were bad; they were just so colossally unmemorable that I could find nothing to say about them. And I didn’t want to bash them just for being mediocre. I thought queer cinema was in a rut and I lost interest. But this year has been something else. In the last months, the offerings have been superb. I’ve watched the Vito Russo documentary, A Portrait of James Dean: Joshua Tree, 1951, August, Weekend and Keep The Lights On. Bad Boy Street wasn’t too shabby either and Judas Kiss' charms are considerable. I’m feeling passionate about queer cinema again. Life got in the way last year and I wasn’t able to review many films. While I was neglecting my website, queer cinema seems to have entered a new Renaissance. Along with August and especially Weekend, (my next review), Keep The Lights On is one of the best new queer narrative films I’ve seen in years. When my Dad died, my writing began to get more sporadic. I also started getting disillusioned by most of the new queer films that I did see. It’s not that they were bad; they were just so colossally unmemorable that I could find nothing to say about them. And I didn’t want to bash them just for being mediocre. I thought queer cinema was in a rut and I lost interest. But this year has been something else. In the last months, the offerings have been superb. I’ve watched the Vito Russo documentary, A Portrait of James Dean: Joshua Tree, 1951, August, Weekend and Keep The Lights On. Bad Boy Street wasn’t too shabby either and Judas Kiss' charms are considerable. I’m feeling passionate about queer cinema again.

|